Neih Ki Yaw, a native of southern Chin State’s Mindat Township, was born a year after Myanmar won its independence from British colonial rule.

He was still a boy when the country first fell under military rule nearly 60 years ago, but was already a father of five (with one more on the way) by the time of the 1988 pro-democracy uprising.

In the 1990s, as the army strengthened its grip after mounting another bloody coup to hold on to power, he lost his wife and struggled to raise his family on his own.

Eventually, he retired from his job as a middle-school teacher and dedicated himself to serving his community. Then, a little over a decade ago, he witnessed the first signs of real change in his lifetime, as the military allowed the first election in 20 years.

No doubt, he hoped to live out his years believing that his children’s children would never have to know the harsh realities of life under a brutal dictatorship. But Myanmar’s military had different ideas.

When the army stole power again in February, for the third time since his birth, Neih Ki Yaw was determined to resist it in any way he could.

Not letting his age stand in his way, he took part in anti-coup protests—and then, as the regime moved to crush all opposition to its rule, he joined the armed resistance movement.

In the end, this decision cost him his life. Earlier this month, a piece of shrapnel from an artillery shell hit him in the back while he was fighting on the frontline, killing him instantly.

His life ended very differently from the way it began—as a citizen of a newly liberated country—but serves as a reminder of the timeless, and ageless, desire for freedom from oppression.

‘Determined to win’

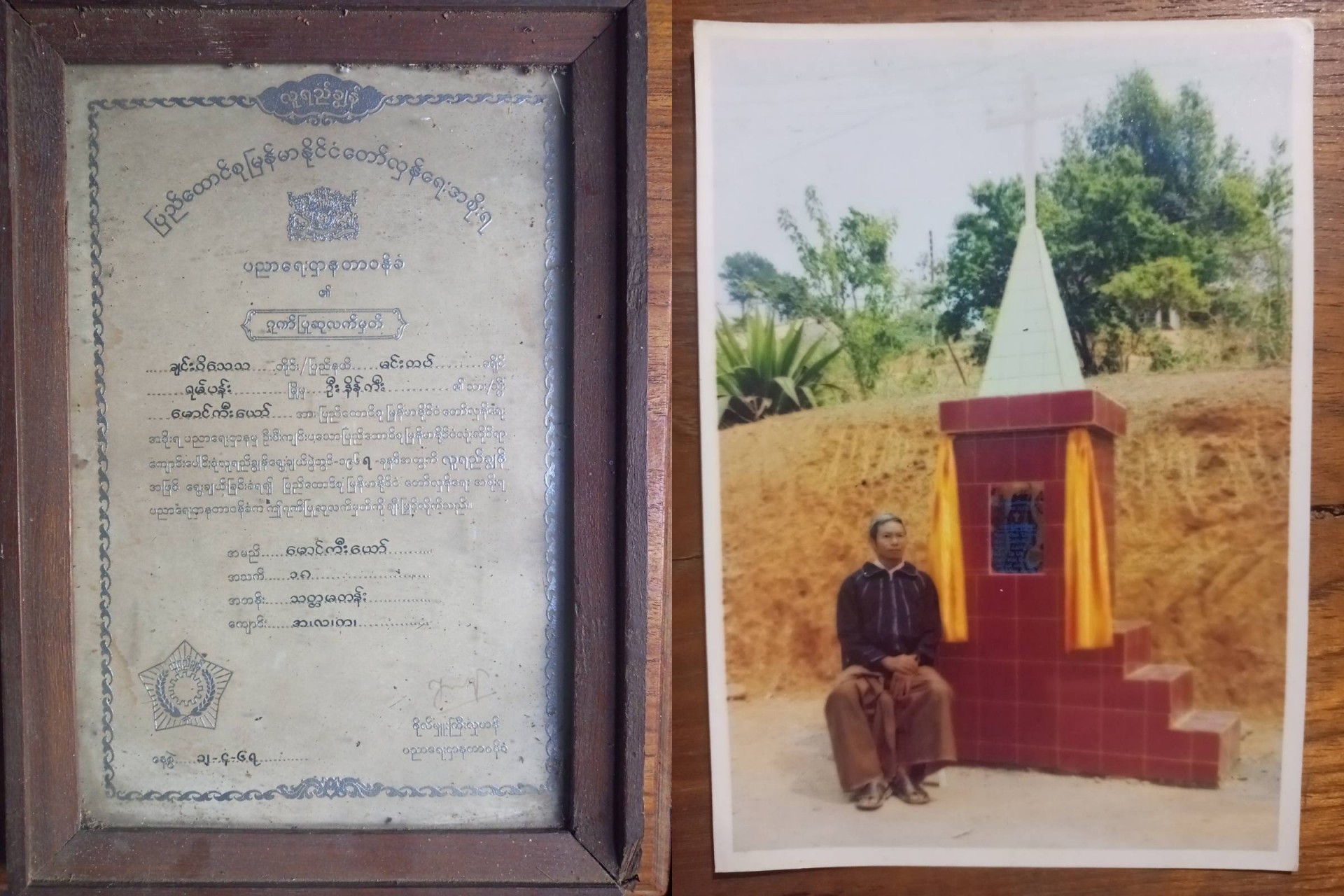

Neih Ki Yaw was an outstanding student in his youth. As an eighth grader, he won an award for excellence, signalling a promising future.

Growing up in Mindat, however, his prospects were limited. As the poorest state in a country that grew steadily more impoverished over the decades due to military mismanagement of the economy, Chin State did not offer many opportunities.

Despite this, however, Neih Ki Yaw remained in the place where he was born and raised, choosing to become a teacher rather than leave in search of better prospects elsewhere.

Our ethnic regions have faced a lot of injustice under all these dictatorships, and he was well aware of this. That’s why he was determined to win this fight at all costs

Many years later, it was this same commitment to his homeland that compelled him to join the fight against a junta that threatens to rob another generation of its potential.

“Our ethnic regions have faced a lot of injustice under all these dictatorships, and he was well aware of this. That’s why he was determined to win this fight at all costs,” said a friend who worked with him to help develop his neighbourhood in Sawntaung, the village he lived in until his death.

Mindat was among the first places in Myanmar to see the emergence of an armed resistance movement. In late April, local people armed only with traditional hunting rifles began to form into small units to defend anti-coup protesters facing lethal crackdowns by regime forces.

Later, these same units coalesced into what would become the Chinland Defence Force (CDF). Over time, they began to fashion more sophisticated weapons, including handmade pistols and improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

As a reserve member of the CDF, Neih Ki Yaw took responsibility for maintaining weapons and making IEDs to be used against military vehicles pouring into Chin State with reinforcements.

“We were so proud of him for playing such a big part in the revolution from his home,” said one of his four sons, a former forestry department employee who quit his government job to join the Civil Disobedience Movement.

Perhaps proudest of all was his youngest son, who took his father’s handmade mines with him when he went to the frontline as part of the armed resistance.

A failed mission

For months, the CDF carried out successful attacks on regime forces using these explosives. However, with the junta’s launch of Operation Anawrahta in October, their efforts to hold back the massive movement of troops proved less effective.

On October 13, a convoy of 70 military trucks and two tanks travelling from Pakokku stopped in Mindat en route to Matupi, in western Chin State. The CDF had laid IEDs along the Mindat-Matupi road to prevent it from reaching its destination, but due to demining and poor weather conditions, only a few were detonated.

When we decided to pull back so that we could return fire, he stayed behind to draw in the junta’s forces. That’s when he was hit

The failure of that mission was a huge disappointment to Neih Ki Yaw, and probably one of the key reasons that he felt a need to go to the frontline, according to CDF spokesperson Yaw Mahn.

“He decided to go to the frontlines because he was afraid his comrades would be hurt by his mines. He was also quite unhappy that they didn’t stop that convoy,” he said.

When the convoy returned to Mindat from Matupi in early November, Neih Ki Yaw left home to join a group of CDF fighters sent to intercept it.

“He didn’t tell us that he was going, but I figured he had already made up his mind. He just gathered all of his weapons and explosives and left for the frontline,” his youngest son told Myanmar Now.

“We didn’t want him to go as he was quite old, but we didn’t try to stop him,” he added.

Fighting spirit

Neih Ki Yaw met his end near Milestone 48 on the Mindat-Matupi road. It was here that he and his comrades came under artillery fire and Neih Ki Yaw decided to sacrifice his life so that others in his unit could retreat, according to Yaw Mahn.

“When we decided to pull back so that we could return fire, he stayed behind to draw in the junta’s forces. That’s when he was hit. A piece of shrapnel penetrated the left side of his back.”

His body was carried back to his home village, where he received a Christian burial at the local cemetery on the morning of November 5. Another ceremony was held for him in Kalay, which has also been a major centre of anti-regime activity. The town, located some 300km to the north in Sagaing Region, also has a large Chin community.

“It was just so sudden. The realization that I didn’t have a father anymore just broke me. But we are proud of him for giving his life for federal democracy, for his people, and for his country,” said his youngest son, the CDF member.

A close friend who asked to remain anonymous said that Neih Ki Yaw was the first person from his village of more than 600 people to die in battle against the junta.

“When the revolution is over, we plan to hold a ceremony to recognize him as a martyr of our cause,” he said, adding that Neih Ki Yaw’s fighting spirit was a source of pride to many living in the Chin Hills.

It was just so sudden. The realization that I didn’t have a father anymore just broke me

His youngest son also vowed to keep his memory alive by continuing the fight until it achieves its goal of ending Myanmar’s decades of oppressive military rule once and for all.

“This is a war and people die during wars. We can’t let his death be the end of our revolution. We will have to continue fighting until the end,” he said.

“We have already decided to end this dictatorship for good. Therefore, we must keep fighting in every way we can,” he added.