PUBLISHED

At a time of growing and widespread armed resistance against Myanmar’s State Administration Council (SAC) regime, the Arakan Army (AA) is now largely in control in Rakhine State. Meanwhile the SAC continues to contest some areas there. As a result, a parallel governance system has emerged. The AA enjoys a greater sphere of influence overall. It has set up a new local judicial system, which has attracted public participation and undermined the status of the SAC’s judiciary. The SAC’s legitimacy and its practical exercise of authority now face serious challenges in Rakhine State.

It is possible to interpret this development as a critical juncture for the revolution. The AA’s success in local governance could be a harbinger for broader success. As a former Karen National Union leader recently shared, in the organisation’s more than 70 years of experience in armed revolution, arms alone cannot determine a revolution’s success. Force must be combined with the functioning rule of law, local governance mechanisms, and public support.

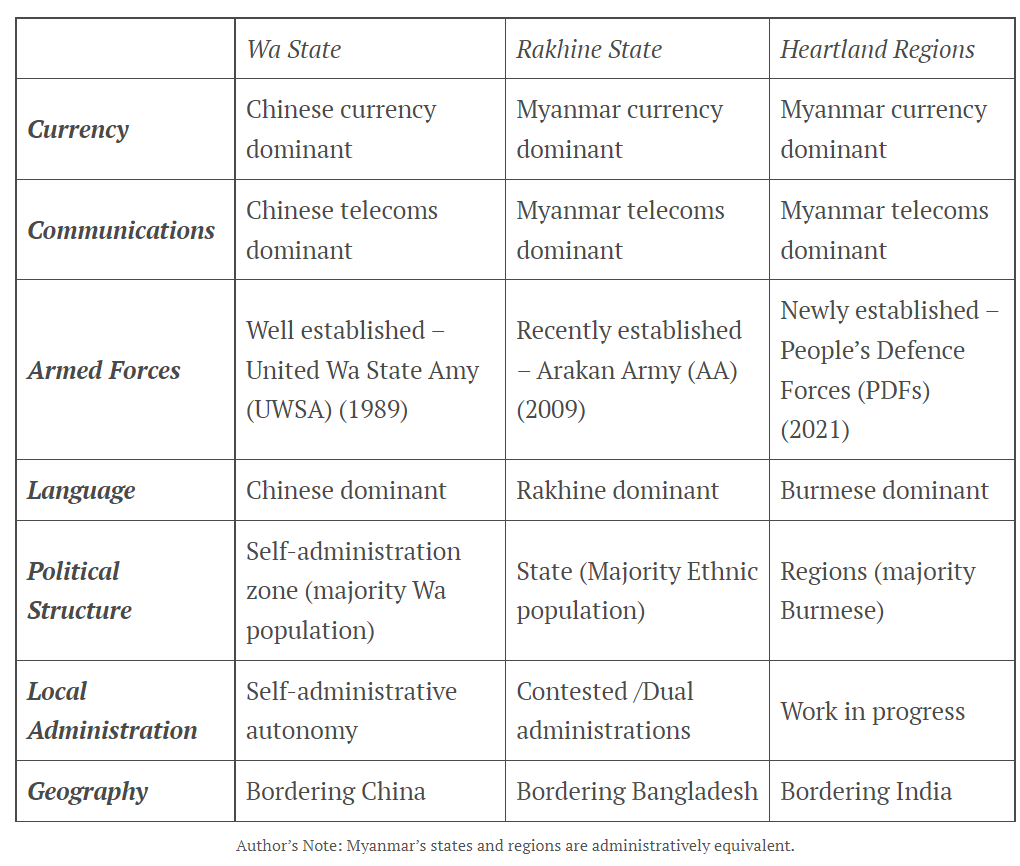

However, the end game in Rakhine State remains unclear. Will the SAC conduct another armed offensive or will it allow the AA to take power and achieve what the AA often characterises as ‘confederation’ or something akin to Wa’s self-autonomy in Rakhine? The Wa State is quite independent from the central government’s administrative machinery and is different from Rakhine. The Wa State uses Chinese currency, the yuan, as its local currency and its internal communications predominantly rely on Chinese telecommunication services. It is harder for the Rakhine to follow suit. While the Wa state has since the 1950s been under China’s influence in politics, economics, border trade including illicit activities, language and other areas, there is no equivalent external force tipping the balance in Rakhine.

A question thus looms: Can revolutionary forces in Myanmar’s heartland areas replicate the AA’s model of assuming local authority on the ground? To answer this, it is important to understand some distinguishing features of AA governance. Foremost is the AA’s judicial control, achieved through active public participation. Many residents including the Rohingya in Rakhine State choose to turn to the AA’s judicial process rather than to courts operating under the SAC’s authority. It is extremely hard for SAC to challenge such public support. Another important feature is the AA’s tax system, where it has levied taxes via a ‘Rakhine People’s Authority’ since December 2019 to fund military, political and administrative activities. Many citizens are happy to pay taxes in support of the revolutionary cause and in the hope of enjoying better services. However, where both the AA and the SAC exert control, certain areas face double taxation. A third feature of AA governance in Rakhine State is the provision of public services. The AA has allowed students to continue studying in state schools under the SAC while an informal ceasefire has been in effect. They pragmatically reason that the younger generation still needs to be educated while the revolution is in progress, and the AA is unable to provide such services. Overall, these tactics suggest that the AA has taken advantage of public support for its ultimate political goal of self-autonomy state or even independence.

The AA’s utilisation of greater public support is a good lesson for the anti-SAC National Unity Government (NUG). The NUG recently claimed to control half of Myanmar’s territory and to have some local authority and control on the ground in the Bamar Buddhist-majority heartland. The question is how the NUG can effectively utilise the support that it enjoys in such areas to establish a parallel local administrative mechanism. It has established People’s Administration Bodies, which it is testing in the Sagaing and Magwe Regions. According to NUG minister U Lwin Ko Latt at a Committee briefing representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw on 18 April 2022, NUG has selected ten out of the 37 townships in Sagaing Region as pilot testing grounds for this intrim local administrative mechanism in judicial and policing work, while another 19 townships will be additional testing grounds. There are six pilot tests in Magwe Region. It remains to be seen whether the NUG will garner the required public participation and enjoy the kind of success that the AA has achieved in Rakhine State.

The successful development of a parallel local administrative mechanism in Myanmar’s heartland would have huge political implications. There is public support for such mechanisms across the nation, even in areas not marked by active armed conflict like the heartland. Figure 1 illustrates the significant differences in local conditions. If those areas can replicate similar models of local administration despite these differences, this will weaken the SAC’s political machinery at large.

Figure 1. Differences in Local Environments for Administrative Control

The development of local administration in the heartland will have external implications as well, especially for China. Significant Chinese investments, including Chinese-run copper mines, are located in the contested regions. The emergence of local anti-SAC administrations will potentially raise a red flag for Beijing, as they could portend a less straightforward process for Chinese investors.

Effective political change can occur in an incremental manner. While these developments may not seem dramatic or destructive, Myanmar’s Spring 2021 revolution may turn on how well a parallel system of local governance quietly replaces the SAC’s authority.

Credit – fulcrum.sg

The Next Phase of Myanmar’s 2021 Spring Revolution Turns on Contested Local Authority | FULCRUM