Since February 1, youth activist and civil society leader Naw Thaboe has supported the National Unity Government steadfastly as it abolished the 2008 Constitution and recognised the Rohingya.

These revolutionary acts convinced Thaboe that the NUG was different from the NLD administration that the Tatmadaw removed from office on February 1. Lately, though, she said the NUG’s bold reforms have seemed to come to a halt.

“In the revolution, people need revolutionary leaders,” said Thaboe, who asked that her real name not be used. “Myanmar needs drastic change, the NUG or any political leaders need to be more proactive and take more radical action against the junta.”

Thaboe echoes the feelings of a growing number in Myanmar who, despite their support for the parallel government, are feeling increasingly frustrated with its lack of progress in establishing itself as a genuine rival administration to the military regime, let alone removing the Tatmadaw from power.

The COVID-19 outbreak has only increased the pressure on the NUG. Although most blame the military regime for the tens of thousands of COVID-19 deaths in recent months, they are also looking to the NUG for leadership to mitigate the health crisis.

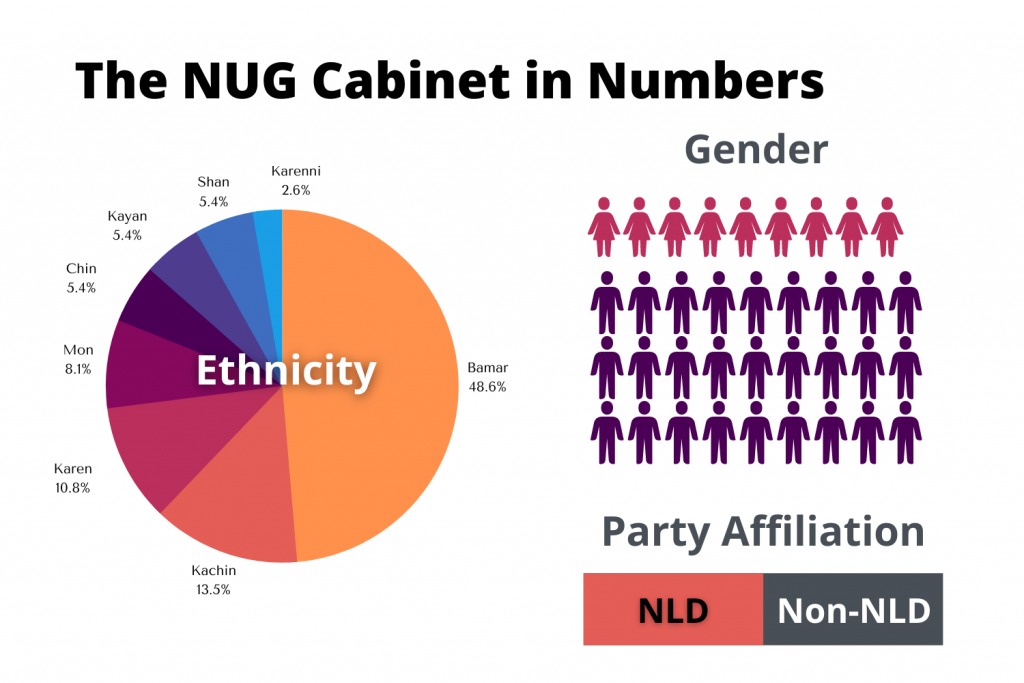

The NUG’s struggles stem in part from deep internal divisions between long-time members of the National League for Democracy and more progressive individuals in cabinet. While the NUG was formed in mid-April by a diverse group that included community and ethnic leaders, the parallel government nominally led by acting president Duwa Lashi La remains dominated by NLD loyalists.

The NUG has “repeatedly stated that it is a revolutionary government first and foremost and has achieved a great deal given the pressure it has been under,” but some activists on the ground increasingly feel like the NUG senior leaders are focused on releasing statements, said Mr Kim Joliffe, a researcher on Myanmar politics and conflict.

“Most revolutionary forces aimed at defeating the incumbent power don’t start off operating like a government,” he said, noting that this strategy was seen as necessary in order to gain international recognition.

“Months ago the NUG had a lot of momentum and it has managed to sustain enough pressure to deny the SAC full control or recognition globally. But it has become increasingly clear that the battle to take full control one way or another will likely be a long and drawn out war, as neither side has the capacity or resources to fully defeat the other yet.”

On August 1, the military regime formed a caretaker government and junta chief Min Aung Hlaing, who appointed himself prime minister, said he expected Myanmar’s state of emergency to run until August 2023, when elections are planned.

Although the military is overwhelmingly unpopular, time might not be on the NUG’s side. If history is a guide, the parallel government faces a growing risk of sliding into irrelevance as time passes. With its iconic leader, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, in detention, a lack of support from neighbouring countries and historic tensions with ethnic minority groups, the NUG will likely need to regain its early momentum if it is to make any major progress.

Unity in name only

This government of “national unity” is yet to be united. Sources within the NUG and those engaged with it say the cabinet has been and remains deeply divided over critical issues ranging from the response to COVID-19, its approach to the economy and cooperation with ethnic communities.

One cabinet member who is not from the NLD told Frontier that trust was “a big challenge” between NLD and non-NLD officials.

“We are still weak in [terms of] collaboration [with] each other,” the minister said, adding that there had been only “very limited talk” among cabinet members on issues such as humanitarian aid and the economy.

The minister’s assessment was echoed by an NLD-aligned official inside the NUG.

“Decades of distrust are not easily overcome in months,” he said.

Ma Phyo, an analyst of ethnic policy who asked that her real name not be used, said there are clearly divisions within the NUG.

“Although there are people from civil society, ethnic people, and activists doing the groundwork and pushing them[NUG officials], sometimes I wonder why it is taking this much to move forward,” she said.

“From my own connections and what I’ve heard, the reality of NLD veterans calling the shots doesn’t seem to have changed within the NUG,” she said.

Ma Phyo also worries that the NUG seems to be overconfident about its ability to prevail over the Tatmadaw, and that popular support could wane if it doesn’t show concrete results.

“It is not helping that NUG ministers are being stubborn, and what’s crazy is that they are so confident that the people will [always] support them because they believe that they are on the moral high ground,” she said.

Exploiting the pandemic

While the junta has tried to exploit the pandemic to cement its control and legitimise its rule, activists and businesspeople in Yangon told Frontier they were worried the NUG was losing touch with the key issues on the ground.

With more than 10,000 officially recorded deaths since the start of June and one of the highest rates of positive tests in the world – at times last month it was above 40 percent – the COVID-19 third wave has inflicted massive suffering in Myanmar. Although the NUG established a COVID-19 Task Force with ethnic health groups on July 21 – a move welcomed by civil society – it has yet to unveil or even outline a policy on the provision of humanitarian aid. This has put international donors and aid agencies in a difficult position, because it is not yet clear what form of assistance is politically acceptable.

The task force has said it plans to focus on bringing vaccines into the country, an approach supported by civil society groups in Myanmar, such as Progressive Voice. The task force has also said ASEAN and the rest of the international community should provide aid through the task force as well as through cross-border channels, community humanitarian networks, and ethnic health service providers. It is unclear if this is advocating for bypassing the junta entirely. Frontier contacted the task force but did not receive a reply.

This policy confusion stems from a lack of agreement within the cabinet, according to a senior official. Some NUG ministers favour allowing donors and social welfare groups to work with junta-controlled local officials as long as they also engage with the parallel government and meet transparency requirements. Others have taken a more hardline attitude, insisting that no aid should go through junta officials.

An ethnic politician and human rights activist, whose name Frontier withheld for security reasons, acknowledged that the NUG was trying its best despite “limited space and opportunity”, but said it still had a lot of room for improvement.

“What people need are two things: the first is political leadership and the second is services,” she said. “The political leadership is very confusing and unclear, with ministers making statements here and there without consulting the others. As for services, they face constraints in their capacity to deliver.”

The lack of consultation is possibly illustrated by a July announcement by the Ministry of Communications, Information and Technology, which said the NUG would accept cryptocurrency donations. The cabinet apparently had not been collectively consulted over the move and concerns over financial transparency were raised, a senior official said.

Whatever the NUG’s capacity, the junta appears to feel threatened by its popularity. On May 5, its Ministry of Transport and Communications imposed a national one-hour internet blackout without warning, seemingly aimed at preventing the public from watching an NUG press conference. It has also frozen bank accounts that have been detected sending money to the NUG and other opposition groups.

Regional powers are less convinced of the parallel government’s influence. China and Russia are sceptical about the NUG’s prospects and have not actively engaged with it, and ASEAN has only engaged publicly with the junta.

A symbol of the past

Aung San Suu Kyi is another factor complicating efforts towards unity within the NUG. She remains a divisive figure among the more diverse cabinet drawn together by the resistance movement in an effort to unite the country, including its powerful but disparate ethnic armed groups, against the military.

When Aung San Suu Kyi was in power, she chastised ethnic armed groups and supported military campaigns against them, defended the Tatmadaw at the International Court of Justice against accusations that it had committed genocide against Rohingya Muslims, and supported an internet blackout that affected more than one million people in Rakhine and Chin states.

“If Daw Suu is released tomorrow and dismisses all the work the NUG has done, it could kill off the democracy movement,” said Ma Ei Ei, a CDM supporter in Yangon who asked to be identified by a pseudonym.

Although Ei Ei sympathises with Aung San Suu Kyi due to her many sacrifices in the struggle for democracy, she said the detained leader had quickly become a symbol of the past after February 1.

“Things have moved very quickly. Daw Suu would face a huge public backlash if she walks out tomorrow and calls the Tatmadaw ‘my father’s army’,” Ei Ei said.

The coup d’etat has also led to an unprecedented reckoning among the Myanmar people. In particular, the deadly force unleashed by the Tatmadaw against peaceful protesters has changed attitudes about the Tatmadaw’s “clearance operation” against the Rohingya in northern Rakhine in 2017.

In an attempt to establish military alliances with ethnic armed groups and seek support from ethnic communities, the NUG has presented itself as a more minority-friendly administration than the NLD’s cabinet and central executive committee, which were for decades dominated by older Bamar men.

Although the NUG has made overtures to minorities, such as the Rohingya policy, the NLD’s track record on minority rights means there is still scepticism from ethnic communities as to whether the NUG represents a real break with the past.

Dr Sasa, who joined the NLD relatively recently and hails from Chin State, is not one of the “old guard” who dominated the party, according to one senior diplomat in Myanmar. The source added that the more conservative, NLD-aligned elements in the NUG were not impressed by Sasa’s progressive politics. Sasa though has a unique position and leverage in the cabinet because he is seen as a part of the NLD and not an outsider, and also because he has built up a public following domestically and internationally since the coup.

Sasa said he would resist any attempt to reverse the stand taken by the NUG to recognise the Rohingya, observing that the military had used divide and rule tactics based on race and religion to create splits in society.

“Our voice matters. They [Aung San Suu Kyi and other detained leaders] cannot just push us into a corner [upon being freed],” he said. Sweeping the NUG’s progressive politics aside and returning to the policies of the past would amount to “political suicide” for any leader, he warned. “I am ready to stand up for what I believe in.”

In a dramatic reversal of Aung San Suu Kyi’s infamous defence of the Tatmadaw at the International Court of Justice in December 2019, the NUG said in late June that it was gathering evidence of Tatmadaw atrocities and was preparing to file a lawsuit for crimes against humanity at the International Criminal Court.

In another departure from the former civilian government’s shunning of the Rohingya, this week saw the first appointment of a member of the Rohingya ethnic group to the parallel government. U Aung Kyaw Moe, the founder and executive director of the Center for Social Integrity, is known in Myanmar for his humanitarian and peace-building work, and was appointed as an adviser to the human rights ministry, Sasa told Frontier.

Differences on policy

Policy disagreements have not been limited to ethnic rights. The NUG’s first budget has been delayed for weeks due to differences of opinion within the cabinet over how spending should be prioritised.

Although the exact nature of these debates is unclear, sources said the forthcoming budget is likely to prioritise aid over defence and spending on the response to a growing humanitarian emergency.

Minister for Planning, Finance and Investment U Tin Tun Naing said supporting the Civil Disobedience Movement would be a top spending priority. “Civil disobedience is an effective weapon that the people of Myanmar can wield in good conscience. It is also the weapon that the military junta fears the most. Equally important is humanitarian support.”

There are clearer differences of opinion within cabinet over foreign investment and how businesses should operate under the military regime.

“There are ideologues who want to take a hard line against businesses that cooperate with the military,” one NUG source said.

But part of the cabinet has a more realistic approach to companies that are in Myanmar and trying to behave responsibly. Tu Hkawng, the NUG’s environmental conservation and natural resources minister, told Nikkei Asia in May that the NUG acknowledged the dilemmas companies operating in Myanmar face if they wish to support human rights. Referring to Norwegian mobile operator Telenor, he said the NUG would not push the company “into a corner”.

Frontier understands Tin Tun Naing also wanted the NUG to take an approach that recognises the difficult position responsible foreign investors now find themselves in, a source in the finance ministry said.

In late July, the NUG finance ministry published a framework for investment in which it said it would not “recognise or honour investment agreements or approvals” made with the military regime since the coup. Those who had invested in the country over the past decade, though, would be treated differently.

“Companies such as Total Energy and Chevron generate a lot of revenue for the military and the NUG has called for steps to limit the revenue flow from them. Telenor has to pay its dues to the military but also does a lot of good for the people,” an NUG source said.

Some large foreign investors are already carefully considering their operations in Myanmar. A few have decided to leave, including Telenor, which announced in early July it was selling its Myanmar operation to Lebanese investment firm, M1 Group, for US$105 million, implying an overall value of around $500 million. The sale represented a significant loss for the Norwegian telco, which had invested more than $1 billion in Myanmar since being licensed by President U Thein Sein’s quasi-military government in 2013.

The hasty sale was widely seen as a desperate move by Telenor to leave Myanmar amid pressure from the junta to use surveillance technology that would allow the authorities to monitor users, said telecoms industry executives.

Tin Tun Naing told Frontier that the NUG regretted Telenor’s departure, but said it reflected the fact the junta had created an increasingly hostile environment for ethical businesses.

“We know that Telenor resisted the military’s pressure to install intercept and surveillance software and share users’ data, unlike the military-controlled operators MPT and Mytel. The company has tried to protect human rights in Myanmar as best it could,” he said.

The Lebanese M1 Group is a controversial buyer, given both its track record working in countries such as Sudan, Syria and Yemen and its links to the Tatmadaw through shares in Irrawaddy Green Towers, a company that has a master lease agreement for its telecom towers with military-run Mytel. Concerns over how M1 would run the business prompted 45 civil society organisations, including Justice for Myanmar, Free Expression Myanmar and Global Witness, to write to Telenor and the Norwegian government this month urging them to stop the sale.

“The NUG’s position on foreign investment is clear. There should be no new investment as long as the junta is in place. Existing investors should stay only if they are doing more good than harm,” Tin Tun Naing said.

The people strike back

The creation of the People’s Defence Force as the NUG’s armed wing in May has also sparked internal debates over the prospects for a united armed insurgency against the junta. Tin Tun Naing declined to say how much funding the NUG was allocating to the PDF, but stressed that its role was to protect civilians and safeguard communities.

“We are not raising a conventional army to wage an all-out war. Our victory will come from the fact that the people support us. Our priority therefore has to be on supporting the people. We will not buy guns if we cannot feed our people,” the finance minister said.

Another cabinet minister admitted that the goal of unifying all ethnic armed groups into a federal army would be extremely difficult. For the foreseeable future, the minister said, the priority was for the PDF to form a federal alliance with other armed groups.

Myanmar analyst Mr David Mathieson says it is too early to predict what direction the new insurgency of the NUG or PDF will take as the situation evolves. But he branded the idea of an alliance between the NUG and ethnic armed groups as a “chimera”.

“Why should they all be under unified command? That is such an NLD mania to control everything and subordinate ethnic grievances to their political agenda: that is partly why the country is in such a mess,” he said.

Not all PDFs are under the command of the NUG, either. While some local PDFs have pledged allegiance to the parallel government, they essentially operate on their own, without assistance from the NUG. Mr Mathieson warned that this could result in a “fragmented” security situation and even a “nightmare scenario” in which “many anti-SAC PDF’s through desperation … engag[e] in various acts of criminality to finance armed resistance … [and] overburden local communities and retard economic growth”.

Defence minister U Yee Mon in early August told Myanmar Now that the NUG plans to unify civilian defence forces throughout the country under one command, and again parroted the “D-Day” narrative, a term hyped up by the NUG in anticipation of an all-out offensive against the Tatmadaw at some future date.

U Kyaw Win, the pseudonym of a Yangon-based political commentator and activist, said the NUG’s constant talk and lack of action about a military offensive was creating frustration..

“The NUG needs to remember that without a controlled territory, there would not be any form of recognition from foreign governments,” he said. But despite a plethora of challenges confronting the NUG, Kyaw Win stressed the NUG is “still the hope for the people, even if we are disappointed in some of their performances”.

“As long as the revolution is not finished,” he said, “the NUG shall have to continue as the frontline political organisation of our revolution.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Irrawaddy Green Towers builds telecom towers for military-run Mytel.

John Liu is a journalist focusing on Myanmar’s politics and economy. He has written for Nikkei Asia, Al Jazeera and other outlets. This story was co-written with a Frontier staff writer.

Source: FRONTIER